Episode Transcript

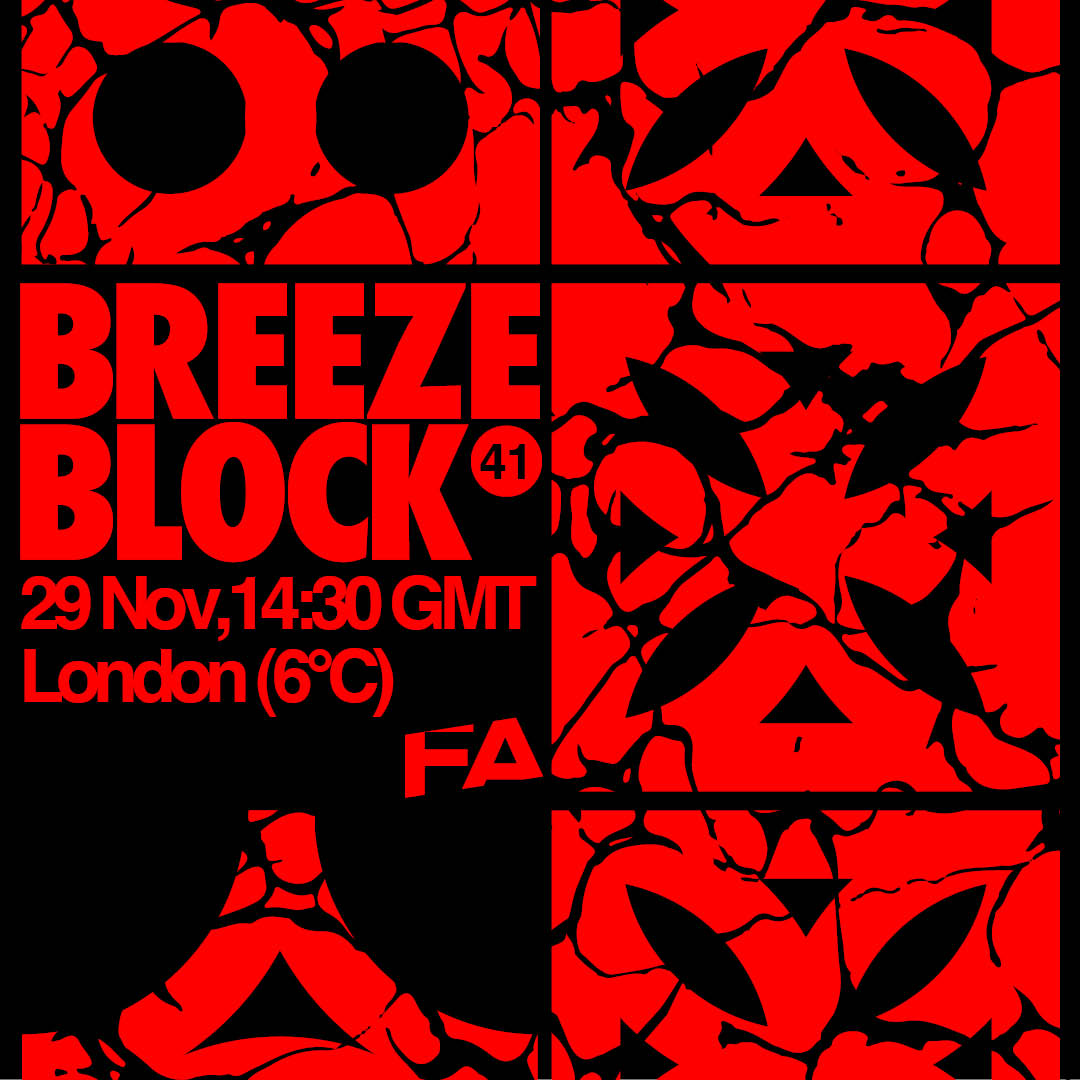

Speaker 0 00:00:05 Hello, welcome to Feld architecture, breeze blocks, where our editors discuss works in progress, urgent matters, and current happenings in architecture and spatial politics. My name's Charlie <inaudible> today. I'm joined by my fellow editor, new editor from the New York team. Kevin Rogen. Hi Kevin.

Speaker 1 00:00:24 Hello. Um, great to be here.

Speaker 0 00:00:27 Thanks. Thanks for having me. Thanks for having me, uh,

Speaker 1 00:00:31 Being here.

Speaker 0 00:00:33 So, um, we're here to talk about, uh, article that you recently wrote for failed architecture. Um, may, maybe it's good to just explain the article in a few

Speaker 1 00:00:43 Sentences. I think that would be nice. Sure.

Speaker 2 00:00:45 Okay. So, um, the article that I wrote is a response to consider is survive Corona virus by, uh, eminent, New York times architecture writer, Michael Kimmelman. And th the piece is in my, in my reading and I'm not very nice to it or to him is, uh, is kind of a disaster in, in ways that I think, what, what am I sort of really favorite things to do is hate read and just read things that I disagree with. And like, instead of giving into the kind of visceral, you know, I don't like this, I don't like this writer or whatever, trying to figure out what it is that doesn't sit right with me. So, um, when I initially read the piece, I, you know, kind of instantly had a bit of a revulsion to it. And then as I, you know, started thinking about it somewhere, I was like, you know, this is obviously kind of like a piece that had to get written just because it's so ideologically perfect that there's no world in which this piece would not come out somewhere.

Speaker 2 00:01:49 It just happened to come out in the New York times. And I mean, the New York times has really been like leaning into the sort of thing I'm thinking anybody, you know, nowadays goes, they're expecting like trenchant radical discourse or anything like that. But, um, this piece really has been sort of the first in a string that have kind of traded off this idea of like, oh my God, the city is empty. Like we've lost some sort of part of what makes us human by forcing us to isolate. Like we can't all come together and sort of repair this supposedly broken social fabric, which I mean is, you know, ridiculous for a ton of reasons.

Speaker 0 00:02:31 So there's this point you make about the emptying out of the city and the loss of community plays into this dynamic that you're exploring in the piece. Right. Of, um, there being two cities as oppose to cities on top of each other. And, um, I take it, the article is going to be titled the city and the city or something along that lines, which kind of plays on China, navels novel of the same name to summarize. It's two cities, Eastern European sort of existing side-by-side where, uh, respective citizens are trained from infancy to unsee each other. Um, and it's obviously a bit like it's been quite a presence in urban discourse for quite a while now. Um, I'd be interesting to talk about the usefulness of the concept, uh, also like how the virus is forced, what would be, I guess, referred to as a breach in <inaudible> terminology between these two cities? Uh, yeah. I mean, just interesting to hear a little bit about how the virus has sort of caused that breach. Yeah.

Speaker 2 00:03:35 Um, so I obviously love that book and that, that particular concept, um, especially because, I mean, really what is so kind of confusing about reading the book is like, these cities are thoroughly intermeshed, it's not like there's one and then there's the other it's, you know, you might be walking down the street and you could be walking through a crowd of people, but they're all, they all belong to the other city. And so therefore your brain just sort of deletes them. You might be walking by buildings that exist in one city and don't and another streets that exists in one city and then another, um, so I mean, yeah, you're, you're totally right. Obviously urban discourse has kind of picked up on this and like ran with it for a long time. You know, I couldn't resist bringing it up again. Um, even if it's just like with the title and the reference, because I think it really does work perfectly, but in real life, there's actually, there's a sort of small caveat that is almost present in the novel, but I don't really remember it being like fully explored to this fact, like, so when you have in the novel, there's the city and then there's the city.

Speaker 2 00:04:41 And one of those cities is quite a bit more prosperous, quite a bit richer, more well to do. Um, and the other is kind of, I mean, it's, it's basically outright sad. It's kind of a shit hole. So that dynamic, I think is actually even more present here where you get sort of bourgeois theorists, like Kimmelman who, when they look out and see the empty city, they're, you know, not only it's, so there's not only two cities existing side by side, but there's like a capital C city that exists only in the mind of the bores RA theorist or writer or artist. Um, that really just looks at the surface level. And I mean, this is very, very literally looking at, you know, in this sense, huge open squares and like shuttered cultural institutions and stuff like that. Um, and seeing some sort of collapse where in reality, there's a whole other city that is more or less working exactly as it has prior to coronavirus even, um, we're work, continues a pace and yeah, it's a bit more dangerous and there will probably be vastly greater rates of infection there, but there is no potential of stopping.

Speaker 2 00:05:53 It is that city that is singularly responsible for keeping the sort of, you know, rarefied Borzois idea of the city as times square as the mat, as MoMA as whatever. Um, just to use my own New York context that keeps that alive, um, in the best of times. And so now that, that has kind of, you know, been withdrawn from and taken away. It's not so much that the SA there's the city and the city in the sense that we're used to, which is always there. It's the divide between, you know, worker and boss, it's the, it's a labor divided, it's a racial divided, it's a gender divided, just cuts straight through all of capitalist society in this case, it's spatialized, um, in a way that is very, very neat almost to the extent where you're like you couldn't ask for a better sort of diagram. Um, and so in this case, just to wrap up, like there is that that sort of tendency exists, but there's only one city that's actually getting looked at and it's the city that came on and lives in. Um, it's not the city of the essential workers of labor or anything like that.

Speaker 0 00:07:07 Um, towards the end of the article, you talk about, um, uh, meaningful communities, uh, not being found in times square or the Ramblas, but in coalitions that protect workers, health and safety. It's a really good point. I'm wondering, you know, since we're both sitting at home while we talk and you know, many of the people listening would also be in that situation, what do you think people like us should be doing? You know, the people who can have the luxury to stay at home should be doing to support and foster these kinds of communities.

Speaker 2 00:07:46 Uh, I, I think there's a ton that we can do. And, you know, I think this is an important point to reflect in terms of tactics, because I think a lot of times people that organize definitely fall for like an almost Kilman style delusion, where it's like about, you know, voting with your feet, it's getting out there, that type of thing. Um, we're, we're sort of convinced ourselves that that is the model that we have to follow. And I think something that we can do at home and we shouldn't be leaving because that just, you know, it's more carriers, that's more potentials for vectors and stuff like that. Kilman talks a lot in his article about solidarity and he uses it to refer to this idea of everybody in one big room together, basically. Um, what we need to look at is solidarity that doesn't look like that.

Speaker 2 00:08:31 So, you know, people like us that are sitting inside right now, like what is crucial is that we do something with our latent political power and like, realize that it's there and realize that there's something that can be done about it. So maybe that looks like for example, um, you know, supporting a rent strike and organizing some servants strike that, you know, people that are still working can't do it. It takes too much time. We have a surplus of time and, you know, that's something you can do over the phone. And, you know, that's just one particular example, but potentially speaking, this could build into something further and further and further. So what is the responsibility of people like us is to do right now is we have to like, sort of keep things running, keep the light on and attempt to move forward beyond something that is just like, sort of sitting inside an ordering seamless or whatever. You maybe just don't do that. Um, uh, and I'm not saying like this is going to breed some sort of like general strike or anything like that, but like it has to start somewhere and the sort of the organizing can happen, you know, while on social distance or in self quarantine. Sure,

Speaker 0 00:09:44 Sure. Nice. Um, so, uh, last question. Um, I was reading, I mean, I kind of jumped on it and it was early on in the article you were, um, talking about like the, this tendency to just sort of see their city as an sort of organic hole or an as a natural process. What does this like tendency to obscure nature, which Kimmelman himself kind of buys into? What does it obscure about what's really going on in the city? Right.

Speaker 2 00:10:13 Um, so yeah, I, I think this is actually like the most important question of all just in terms of where my head was at while writing the piece. My point of departure is sort of found in, um, Neil Smith's uneven development, um, where he spends the first, like at least sold chapter, maybe more just kind of talking about like conceptions of nature that are built up and required in order to like, think about the way, and it's not nature so much as it is a nature that weirdly enough, perfectly conforms to like the ideological precepts of capital. So it's like nature is like chaotic, self-organizing emergent structure, that type of thing. Like it's a process obviously, but it's something that you, that arrives at after a long sort of Darwin, Darwin influenced period, and that idea of evolution really, I think kind of occupies of time of like the sort of processing bandwidth of these types of people that conceive of cities as natural objects.

Speaker 2 00:11:17 The other thing I wanted to focus on really quickly, if that is, this is, I mean, it's really, really a classic textbook example of like just the phenomenon of reification, which if, if you're familiar with ratification or anything like that, when you, when you start thinking of a city as an object, like here is New York city here, here is, you know, Berlin here is wherever. It just instantly evaporates the very sort of tenuous and fraught relations that build that and keep it running, build that historically, um, and keep it running now. And, you know, when pressed everybody sort of, I think, agrees with this, like nobody would really think of like a city as a single object, you can pick up in your hands or anything like that. Like, obviously it's very different, but you know, it's still a very sort of influential and the sort of pernicious view of things.

Speaker 2 00:12:13 And even, I think sort of modern urban theory that sort of, instead of thinking of the city as an object or of the city as a natural object, just especially, um, so approaches that more an academia world think of like the city is like a sort of structure of flows and like, things like that, those are basically the same thing. It's still the sort of verified idea of what, what nature does. So like, so we can ratify complexity, we can ratify relations, we can reify systems and pretend that we're actually talking about the way things are. Um, when in reality we've just created another layer of mystification. Um, I don't think element is quite that nuanced or complex, but this is something I, and I've seen a ton. I'm sure you have too. I'm sure there's way better examples that I'm not thinking of right now, but what can you do?

Speaker 0 00:13:05 Yeah. Nice. Um, no, it's totally, I, I, it it's, uh, maybe something that's quite difficult for people initially to get their head around this, this, you know, there is an attraction to the metaphor of kind of flows and often like kind of fluid, liquid water metaphors and things like that, you know, in order to sort of, you say kind of re things that are entirely contingent upon sort of, um, relations of production or, or, uh, to, to sort of maybe, um, dip in dip my toe briefly in this sort of Marxist terminology,

Speaker 1 00:13:42 Very hesitantly.

Speaker 2 00:13:43 Then just go ahead and dive in.

Speaker 1 00:13:46 Um, maybe for next time.